One of my primary research areas is inverse problems in imaging. Often in casual introductions, I will just say I work on imaging systems. People are generally familiar with, or at least aware of, microscopes, medical scanners, and cameras, and I do not need to ramble on any longer than appropriate in new company. But while I love the applications of my research, what makes it so fun to do is almost entirely on the inverse problems side. So this post is my attempt to explain the less understood half of my research.

Put simply, inverse problems refer to all of the difficulties you encounter when you have a noninvertible function, but you have decided to try to invert it anyways. As a simple examples, say you take a number, square it, and the result is 4. What was the number? We could write that as Often the answer that comes to mind is 2. That is what the square root of 4 is after all! But this is not the only possibility, and you may remember that -2 squared is also 4. Which is the "right" answer? It depends.

For such a simple problem, context will often be a sufficient clue. If we knew 4 represented the area of a square, and our unknown is its length, then it would be reasonable to expect our unknown to be positive. In this case, it was straightforward to convert the context ("area and lengths") into a mathematical constraint on the solution (a positive number).

In general, converting the context of an inverse problem into math is challenging. In imaging, our context can be as broad as "a real image", and so we are tasked with describing mathematically what a "real" image looks like.

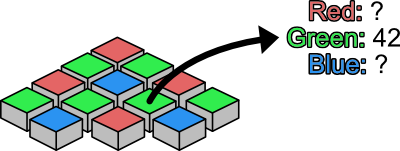

Almost all images of real-world scenes are estimated to some degree. MRI scanners must compute an image from radio waves, a CT scanner computes a volume from x-ray shadows, and telescopes leverage multiple measurements to increase resolution. These processes almost always include some ambiguity that makes it an inverse problem. For example, most color cameras have sensors where pixels can only measure a single color each, but when we view an image, every pixel is represented in full color. Since pixels in real images generally have colors similar to neighboring pixels, we can use this context to estimate a full color image. The math term for this similarity of neighboring pixels is smoothness.

An important thing to note -- which makes describing real images even more difficult -- is that every assumption will limit what our estimated image is able to be. To take the previous example, if we assume colors vary smoothly across the image, then we cannot estimate an image where every pixel has an independent color. Thus, there is a trade-off between the strength or specificity of a modeling assumption, and the bias it adds to the estimate. Smoothness is a relatively weak assumption, and so its effect on the estimated image when it is wrong is relatively benign as well: a slightly blurred dog still looks like a dog to most people. Combining this with the belief that real images really are smooth makes this a popular and now classical model of real images.

In contrast, more modern mathematical models for real images will employ artificial intelligence. These models are powerful and allow for estimating images in even more ambiguous circumstances. While classical models like smoothness were generally too broad leading to little strength and minor biases, these newer models are overly specific and tend to suffer from bias problems. A notable example of this was the PULSE algorithm, which tries to estimate a high resolution image from a lower resolution image and was biased towards resolving people as Caucasian (see e.g. reporting by the Verge).

The challenges fuel some of the more recent research in inverse problems for imaging, but there are many more problems that I have not gone into here, such as how do we design and employ these models in a computationally feasible way, and how do we measure the performance (and the bias) of these algorithms? As we continue as a society to advance in our need for high quality images in a variety of fields, these challenges and trade-offs will be important to consider.

Cameron Blocker

Cameron Blocker